Telehealth Takes Center Stage During COVID-19

Patients now have more access to care than ever.

Stephanie Kiser, B.S.Pharm., R.Ph.

Stephanie Kiser, B.S.Pharm., R.Ph.

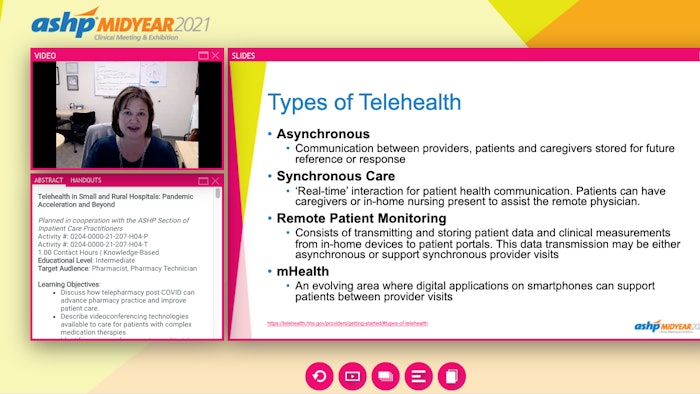

“COVID flung us all into the telehealth space immediately, and the infrastructure was not there, policy changes were not there,” said Stephanie Kiser, director of rural health and professor of pharmacy at the University of North Carolina Eshelman School of Pharmacy and director of interprofessional education at the Mountain Area Health Education Center (MAHEC) in Chapel Hill.

Kiser opened the on-demand session Telehealth in Small and Rural Hospitals: Pandemic Acceleration and Beyond.

Kiser said healthcare providers struggled with digital platform privacy, security, ease of use, workforce shortages, and training to make telehealth a reality. She said things couldn’t really come together until the infrastructure was there, which includes policy and reimbursement. Telehealth waivers from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) were crucial to making this happen.

“This is how things started moving very quickly so that we could conduct telehealth with patients located in their homes and outside of designated rural areas,” Kiser said. The waivers allowed providers to bill for telehealth (both video and audio only) as if the services were provided in person. This meant providers could practice remote care even across state lines, through telehealth, to both established and new patients.

Kirsten Stone, Pharm.D.

Kirsten Stone, Pharm.D.

In this phase, patients visited an onsite exam room at their local clinic — the originating site. This site had a telehealth cart with a computer, video camera, and speakers. A nurse checked vital signs and started the connection with a remote provider, making the introduction. The remote provider was located at their home clinic.

“Although sometimes clunky, this process was a new means for patients to be able to receive services not previously offered at their own local clinic,” Stone said.

Early challenges included connectivity, timing, and tracking appointments of for two schedules, one for the provider and one for the equipment. Over five years, Essentia Health telehealth grew from a few hundred annual encounters to 5,000, with nearly 350 providers offering care for allergy, chronic pain, medical weightloss, infectious disease, speech, behavioral health, and more.

Ambulatory care pharmacy joined Essentia’s teletherapy group in 2015 with the Essentia Health COAT (chronic opioid analgesic therapy) program, designed to help battle the national opioid epidemic by assisting in the tapering and discontinuing of high-dose or inappropriately prescribed opioids

“It was at this time that we were able to spread organizationally our first well-established Pharm.D. collaborative practice agreement for opioid tapering and discontinuing,” Stone said.

In 2015, Essentia Health had only four medication therapy management (MTM) physical locations, with 1.8 full-time equivalent pharmacist clinicians spread across the sites. All were centralized in the same area. There was little organizational awareness of ambulatory clinical pharmacy services at this time, Stone said.

“Within one year, we nearly quadrupled our spread by providing services to nine new clinic locations, all supported through telepharmacy,” she said.

Fast forward to spring 2020 when the pandemic hit. As with other health systems, at Essentia, healthcare delivery was turned upside down, Stone said. Elective surgeries were cancelled, patients refused general medical care due to fear of exposure, and staffing levels were up and down. For support and visibility, Essentia kept its pharmacist clinicians onsite at clinics but limited face-to-face visits.

“With so many hurdles in healthcare, it was now more than ever that patients and providers needed our pharmacy services. Thankfully, with Telehealth Phase 2, this was quickly a possibility,” she said.

With Phase 2, telehealth technology included many more options than Phase 1, which limited patients to onsite visits at two clinic locations. Virtual video visits were implemented for patients who had smartphones or computers with visual capabilities and could thus connect with providers without leaving home. This service expanded appointment options for primary care, behavior and mental health, orthopedics, substance abuse, physical therapy, and heart and vasculature.

Rebecca Grandy, PharmD, BCACP, CPP

Rebecca Grandy, PharmD, BCACP, CPP

“We did do some telehealth via telephone,” Grandy said. “For example, if we had a patient who needed an insulin titration but we didn’t want to have to bring them back to clinic every single week, sure, we would call them on the phone and do a titration. But we did not bill for it, it was not systematic. We were just doing it as part of good patient care.”

When COVID-19 hit, everyone who did not have to be physically onsite at MAHEC was sent home. That included the entire pharmacy team and many medical providers. Everything that could be converted to telehealth, was.

MAHEC went from 0% telehealth in February 2020 to 100% by April 2020.

Grandy described the implementation obstacles the education center encountered, including scheduling, choosing a telehealth platform, and getting billing up to speed.

In North Carolina, clinical pharmacist practitioner (CPP) status allows pharmacists to bill for services using evaluation and management (E/M) codes. CPPs work closely with coding auditors to ensure that provider encounter notes support billing for telehealth, Grandy said.

“For billing, video visits are actually really easy,” she said. “Bill as you would a normal encounter using traditional E/M codes.”

Billing is trickier for phone visits, she said. In North Carolina, pharmacists can’t bill Medicaid for phone visits. For Medicare and commercial payers, pharmacists bill using incident-to codes

“The general theme is that most insurances prefer video; however, you all know that since you are working with rural populations that that’s not always possible,” Grandy said.

As COVID-19 fears have eased, MAHEC is now at 10% telehealth, including video and phone services. It’s really been a matter of patient preference, said Grandy, adding that she imagines that number won’t change much moving forward.

“The biggest reason we only have 10% telehealth now is that our patients want to come to the clinic,” she said. “This is especially true for our older patients who face a lot of social isolation. They just want to come and see real people.”

Find resources, including information about ASHP’s advocacy efforts related to telehealth, AJHP articles, and the ASHP Pharmacy Executive Leadership Alliance Telehealth Innovations Conference Report, in ASHP’s telehealth resource center.