Anti-Racism and Its Role in Achieving Health Equity

COVID-19 has disproportionately impacted communities of color.

Pharmacists can help reduce or eliminate health disparities through anti-racism and proactive work to uncover their patients’ social determinants of health, experts said during one of the Midyear Clinical Meeting’s sessions dedicated to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI).

“In today's environment, it has been said that being well-meaning and not racist is not enough, it is time for us all to be anti-racist,” said Paul Walker, clinical professor and assistant dean of experiential education and community engagement at the University of Michigan College of Pharmacy.

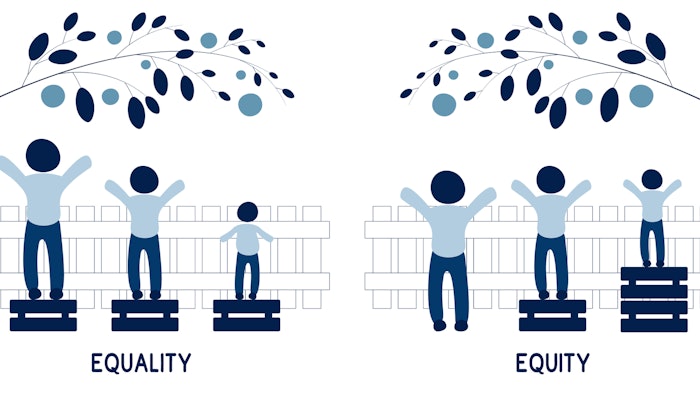

Walker, who served as chair of ASHP’s Task Force on Racial Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion and is the president-elect of ASHP, opened the session “The Pharmacist's Role in Promoting Healthcare Equity and Anti-Racism Practices” with a discussion of health equity, which is achieved when every person has the opportunity to attain their full health potential and no one is disadvantaged from achieving this potential due to their social position or other circumstances.

From left: Lakesha Butler and Paul Walker

From left: Lakesha Butler and Paul Walker

An overwhelming body of literature documents significant racial and ethnic disparities in health and healthcare, Walker said, most recently seen with COVID-19, which has disproportionately impacted communities of color. Additionally, research into publicly available COVID-19 vaccine distribution plans has shown that most were created without the advisement of representatives of color who could help devise equitable vaccine rollout plans.

Historically, racial disparities exist with other diseases such as cancer, diabetes, asthma, and others.

“The major underlying reason for these disparities that continue to be documented in health and in health outcomes is structural racism,” Walker said. “Structural racism also shows up in implicit or unconscious bias in clinical decision-making and also in the education and training of healthcare professionals.”

Pharmacy-specific DEI concerns include racial or ethnic disparities in medication management, Walker said, referencing a study published in AJHP that examined variations in the medication treatment received by racial and ethnic minorities. For example, that study found Black Americans and native Alaskans were significantly less likely to receive and to fill prescriptions for long-term asthma control.

These disparities in medication use may be attributed to cost and lack of access to pharmacies and pharmacy services, which can often be the case in predominantly minority communities, Walker said.

To improve health outcomes for patients of color, Walker said, it’s important for pharmacists and other healthcare providers to educate themselves on the concepts of anti-racism and be an anti-racist.

“This concept is not new and has actually been around for several decades, but it's experiencing renewed interest, particularly in healthcare circles, because of a heightened awareness of health disparities,” Walker said. “Anti-racism is defined as the policy or the practice of opposing racism and promoting racial tolerance. It embodies practices and policies that are focused on dismantling structural racism, and that's a really important key to grasp.”

Practicing anti-racism takes a lot of self-reflection, said Lakesha Butler, professor and director of diversity, equity, and inclusion at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. Anti-racism should also be part of the discussion in the workplace; for example, supporting and validating the comments of historically marginalized individuals and taking a personal interest in the lives and welfare of individuals of different social identities, she said.

“It’s also important for us to recognize and learn about the structural and systemic barriers that exist within our immediate network of influence within our workplace, and that does take education,” Butler added. “It certainly does take time reviewing policies and procedures, utilizing experts in the field to help uncover those particular structural and system barriers, because if we have been benefitting from those particular barriers, then it's very hard for us to recognize them.”

The first step toward dismantling racism is learning about the history of African-Americans and the Black experience, Walker said. It’s also important to see each person’s individuality, and in the healthcare setting, this means seeing each patient’s individuality.

“Patients may struggle with social issues and challenges and require support in various areas at different stages in their lives, and we can best help them by seeing them as individuals and responding to their needs,” Walker said. “And we must also cultivate empathy for others, especially for our patients. Asking about social issues in a caring, empathetic way is important. The evidence indicates that compassion and empathy make patients more forthcoming about their symptoms and concerns, yielding more accurate diagnoses and better care.”

Butler said it's important for pharmacists to incorporate social determinants of health into comprehensive medication management.

“We are the medication experts and we oftentimes will take care of patients who are not controlled with their disease states,” Butler said. “We may think that it’s due to decisions that are made by the patient, but certainly we know that there are determinants or factors that we need to uncover.”

Collecting and uncovering patients’ social determinants of health is not a commonplace action that most pharmacists or healthcare providers take, Butler said, but it’s the first step toward understanding the barriers that are contributing to the patient’s management of their disease state.

“Some pharmacists may find this to be challenging because they don’t necessarily know exactly how to ask the question,” Butler acknowledged, so it requires building a relationship and trust with the patient first.

Healthcare providers who do the work to establish relationships and dig deep are better equipped to care for their patients. For example, one might learn that a patient is living in an environment that exposes them to toxins that could be a factor in uncontrolled asthma and then work with an interprofessional team including social workers to address factors that are having a negative impact on their health, Butler said.

A social needs screening tool from the American Association of Family Physicians may be used as a resource or starting point for those who are not sure what questions to ask.

Walker and Butler also discussed the importance of educating student pharmacists on social determinants of health. The report of ASHP’s Task Force on Racial Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion includes recommendations for ongoing education within colleges of pharmacy and accredited residency programs regarding the value of cultural competence in improving health outcomes of underrepresented minorities.

Supplemental reading on this topic in AJHP includes The Disease of Racism and Role of the Clinical Learning Environment in Preparing New Clinicians to Engage in Quality Improvement Efforts to Eliminate Health Care Disparities.