Pandemic Adds to Burden of Burnout

Two years into the crisis, the burnout continues.

Dreading work that once brought joy. Working harder, for longer hours, with fewer resources. Giving it all but no longer getting by. These are descriptions pharmacists gave when asked what burnout means to them, during the Dec. 5 Midyear session “Sick and Tired of Being Sick and Tired: New Perspectives on Occupational Burnout During the COVID-19 Pandemic.”

Session Chair Bryan McCarthy, director of inpatient pharmacy for Lifespan in Providence, Rhode Island, said health professionals in recent years have recognized occupational burnout as a growing concern, driving efforts to better understand and address the problem.

McCarthy said burnout worsened with the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic, as clinicians logged endless hours only to see patients sicken and die despite heroic efforts to help them.

“There was absolutely no playbook for all of us on how to handle this,” McCarthy said. “The pandemic has really ravaged our professional and personal lives to a degree that we’ve never seen before.”

Two years into the crisis, burnout continues to affect frontline healthcare workers who are challenged to do more with less. And McCarthy said the feeling of relief when vaccines first became available a year ago has given way to dismay about a public health climate that’s prolonging the pandemic.

“This is where we are today. And frankly, we’re getting sick and tired of it,” McCarthy said.

Session presenter Lalita Prasad-Reddy, assistant dean for student affairs at Chicago State University College of Pharmacy and clinical pharmacy specialist at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, Illinois, described burnout as “a state of mental and physical exhaustion related to caregiving activities.”

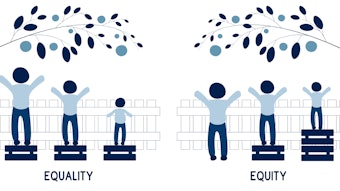

Prasad-Reddy said emotional exhaustion, a reduced sense of personal accomplishment, and feelings of depersonalization are indications of burnout in the workplace. She said specific drivers of burnout include challenging patient cases, high workload, inadequate support to meet that workload, skewed work–life balance, loss of autonomy, and mismatched values between organizations and caregivers.

“Increased job demands with decreased resources to [meet] those job demands is often the perfect recipe for burnout to occur,” Prasad-Reddy added.

Prasad-Reddy and McCarthy said self-care and mindfulness remain solid personal strategies to foster resilience and limit the effects of burnout. But healthcare organizations also need to develop and implement plans to protect their staff from burnout and ensure better care for patients.

Prasad-Reddy said organizations should acknowledge that burnout occurs; provide training, mentoring, and resources, such as peer-support networks; and connect with staff to find creative ways to meet their needs.

“Make sure that everybody has a voice at work,” she added. “Recognize accomplishments.”

When possible, she said, modify work schedules so staff have time to unwind outside of the workplace and refresh themselves before returning to their job.

Several pharmacy staff who submitted video vignettes for the session said taking time off and shedding vacation guilt has been the best prescription for their own feelings of burnout.

A pharmacy technician who identified himself as Terrell expressed that sentiment best.

“If I can get two days off in a row, then I will be OK,” he said.

For AJHP resources on this topic, see Burnout and Secondary Traumatic Stress in Health-System Pharmacists During the COVID-19 Pandemic.